Teresa De Gennaro is a seasoned performer from sunny Australia with a spring in her step and a smile that can light up any room. She also has Multiple Sclerosis (M.S.), a neurological disease with both painful and, at times, debilitating symptoms.

Her twenty-year career has taken her around the world, performing on cruise ships in the Mediterranean and South Pacific, as well as travelling extensively throughout Europe and Asia. She has lived in cities such as Sydney, Rome, London and her dream destination, Los Angeles (California). Having hidden her M.S. from casting directors and fellow actors over the years, De Gennaro recently created her own one-woman show which depicts her experience as a working actress living with M.S. and also aims to destigmatise neurological diseases.

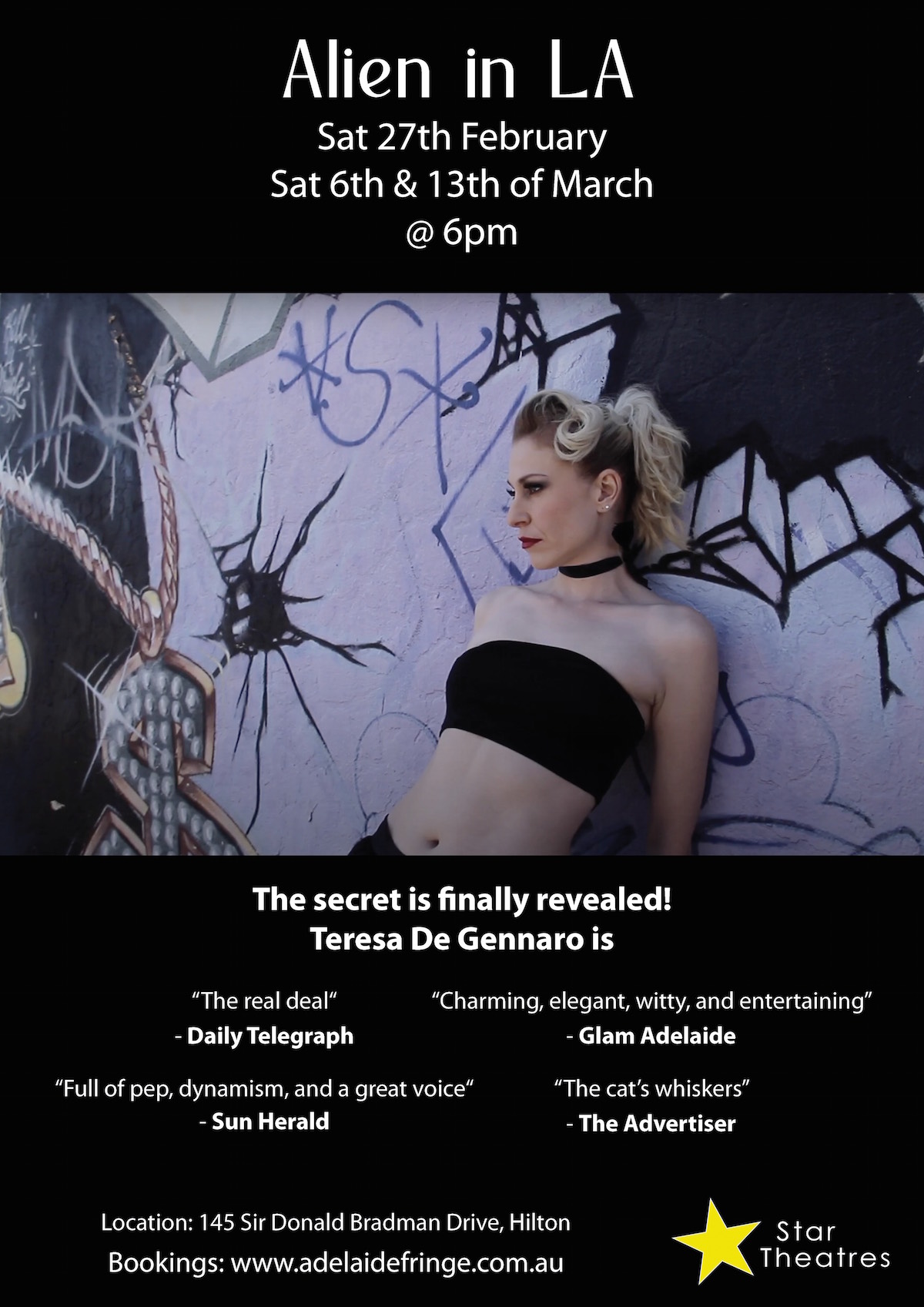

‘Alien in L.A.’ featured in both the Back to Back Festival (Adelaide, 2020) and as part of the Adelaide Fringe Festival (Adelaide 2021), both playing to a limited capacity due to Covid-19 restrictions. The show has garnered rave reviews, prompting plans for a future Australian tour, an online version of the show and an appearance at the world-renowned Edinburgh Fringe Festival (U.K.).

Speaking to The Giant Peach, she recounts achievements, losses, dreams and harsh reality checks with a candid wit, whilst sharing vital pearls of wisdom – opening our hearts and minds to the physical and social challenges faced by people who have M.S.

“I’d tell the kids at school that I was Drew Barrymore and that when I went to L.A. I was acting in the E.T. movie.”

Teresa De Gennaro

Where did your journey into show business begin?

It actually started in Los Angeles as a six-year-old. I visited Disneyland, Universal Studios, all those places. It’s something I explain in the show – I just had that feeling, like, ‘I’m gonna come back one day and become a movie star.’ It was really that childlike fantasy. I’d been attending dance lessons already and I was a real show-off around the house (laughs). Even when we went to Italy to visit family, any excuse to stand up on the table and sing, I’d be doing it.

I so wanted to be in E.T. You know the Drew Barrymore character? I’d tell the kids at school that I was Drew Barrymore and that when I went to L.A. I was acting in the E.T. movie. I really just wanted to fulfil that dream. So, I set out to learn as much as I could about the craft, to get myself prepared for living and working there someday.

What is it about L.A.?

The creative energy there is just buzzing. The competition is tough, but the drive is so contagious. Opportunities are everywhere, even when you’re going out socially. You never know who you’ll end up talking to, what information you might find out about any new classes or auditions. I mean, you can meet someone at the bus stop and they’ll have been in acting – I’m the kind of person who’ll talk to someone at a bus stop (giggles).

But, yeah, it’s just that magical vibe, like anything could come from around any corner at any moment. I used to love that I’d go to a local bar and there’d be Grammy award winning artists playing. I’d go out during the week a lot, just to see these people sing. As a performer, it was a real education. And the work ethic is phenomenal – actors there are in training every week. It’s like, you’ve got a dream, you work for it, you go for it. It’s a real way of life – I love that attitude.

In a way I fulfilled my dream by living and working there already, but I really feel as though the story hasn’t ended. I will return when travel is less problematic and hopefully get my green card.

When did you find out that you had M.S.?

I started to get symptoms around late 1996, so I was only 18. I’d already got into acting school and, a few months beforehand, I became unwell. We didn’t know what it was – it took 6 years to reach a diagnosis. So, my whole time at acting school was good days, bad days, having to get extensions on essays, etc. I managed 5 years of university and then, a year later, my symptoms increased. I’d lost a lot of feeling and also gained pain in my legs. When I started to lose feeling in my hands, I finally had a brain scan and we discovered that it was M.S. I was told that I had about 5 years and then I’d probably be in a wheelchair because that’s what the statistics told us at the time.

Thankfully, since then, medication has drastically improved and saved a lot of people from further disability. I mean, when I was in London, I was having to inject myself every second day, my immune system was down, I had flu-like symptoms all the time, so I’d constantly be taking paracetamol, which was wrecking my liver. Now, I’m on tablets with minimal side effects. There’s apparently an infusion medication on the way which can give you 6 months without any tablets going through your stomach. So, things have really changed.

“I definitely think it’s my most genuine piece of work.”

Teresa De Gennaro

How did you deal with the initial shock after being diagnosed?

I’m sure I had my cries and despondent moments but, basically, I just clicked into gear. I was like, ‘I don’t have much time, so I’ve gotta get my shit together and try to experience what I want to experience before I’m disabled.’ I said to my partner ‘I’m going to Sydney to work on my career asap.’ Luckily, he was able to come with me so that’s what I did. When I was there, I took the opportunity to work on the cruise ships.

Five years later, I was still doing alright. I was on some hard-core medication that we didn’t know the long-term effects of. It was a new thing out at the time and part of some medical trial. I just kept going. It was really that initial prognosis that drove me to see as much of the world as I have. My moto was always, ‘I’ll do what I can, while I can.’ And, yeah, it seems like I haven’t stopped (smiles).

I attended some group therapy which was devastating but also quite empowering. I remember someone who was completely blind which was terrifying to think that that could be a possibility. Another young girl was in a wheelchair, people would talk about how they were incontinent – it was all very confronting and, at times, I thought, ‘What have I got to look forward to?’ One time, a lady got up to speak and she’d brought with her a pair of flamenco dancing shoes. She put them on the table and said, ‘I thought I’d never be able to dance again but I went to Spain and I did flamenco dancing.’

That really stayed with me, just that she’d told herself that it wasn’t gonna hold her back. It was a real defining moment.

How have you adapted your show to meet your physical requirements?

I had a director this time around who was very aware of my restrictions and we staged it to fit my needs. It’s a one-hour show with a lot of songs, but I use a verse that’s pertinent to the story from, say, a Eurythmix song and then throw in a chorus of something elsewhere. So, I never sing any song in its entirety because that can be quite exhausting for me. I also figured I didn’t really need to do it in that way, as the story is the main focus of the piece.

There’re three chairs on stage, so I can wander over to one chair, stand up for part of a song, sit down, perform a monologue. I mean, I’ve always been that kind of cabaret type performer anyway. I get bored of a whole song myself (laughs).

I definitely think it’s my most genuine piece of work. I don’t know how but, after 3 tumultuous years of bad health, my voice was just there. It’s really in good shape right now. I mean, sure, I don’t have the top range I used to have 20 years ago, so a few songs I’ve lowered the key, but my control over my instrument has really surprised me. I’ve been told by other female performers that they noticed their voices improve into their forties. I think that’s what I’m experiencing, that richness of sound that I didn’t really have before and a feeling that I’m very much in control of what I’m doing.

As we enter into small talk before starting the interview, De Gennaro informs me that the last week has been her best in 2 months. ‘I did have a little nanna nap’, she says jokingly, ‘but I’ve been really active today. It’s been good.’

Three days before her final performance, she experienced new symptoms. ‘All of a sudden, I woke up and, in the back of my head, I felt this huge amount of pressure. It started to become pins and needles and eventually my ear went completely numb. Then it spread over my face and down the left side of my body. I had to do the last performance with all of these sensations.’

I ask how she got through it and she responds without missing a beat. ‘Well, I just tried to ignore it because I knew what it was, and I knew if I were to admit myself to hospital then I’d be staying there for some time and I wouldn’t be able to do the show.’

After soldiering on, De Gennaro was admitted to hospital the following day where she spent 3 weeks on steroid medication. ‘When it affected the left side of my body, my leg didn’t quite know where to go, so it affected my walking. But I’m walking pretty good now. Before the show I could walk for 14 minutes straight but now I can only do 6 minutes. So, my aim is to get back to those 14 minutes and then hopefully push past that.’

“Just because someone doesn’t ‘look disabled’ doesn’t mean that they aren’t suffering or having difficulties.”

Teresa De Gennaro

Would you say that performing helps you to overcome your symptoms or can it trigger them at times?

It’s hard to say – it can swing both ways. When it’s crunch time, every bit of focus, every bit of energy, every ounce of your being is in that performance. So, I do experience more pain while I’m in that mode.

But, equally, the distraction overcomes that extra pain. Despite the fatigue you have that adrenalin rushing through your body. Sure, I’m suffering a bit while I’m doing it, but I’m also getting so much out of the endorphins.

With M.S., even just going to the shops you’re pushing your boundaries all the time, so why not do something you enjoy? I did a Judy and Liza show years ago and the research I did was so inspiring. There were problems with relationships, alcohol, drug addiction, yet they still managed to get on stage and do a 5-star show. I thought to myself, ‘They’re like, half-dead and they’re out there doing it, so I can do it too.’

What do you hope that audiences will take away from having seen your show?

I hope it’ll inspire – not only people with disabilities but people without as well, to help them see and hopefully appreciate their fully functioning bodies.

It really shocked some of my friends seeing me in a wheelchair. Normally, when I go shopping on my own or I’m doing things where I have to stand a lot, I bring the wheelchair with me, but most of them haven’t seen me in it. After I brought it out on stage, a lot of them said things like, ‘That was when my heart just dropped’. The response in general seems to be that they found the show inspiring, but I think it’s been good for them to see the downside too.

I’d hope to educate people about the invisible aspect of M.S. Just because someone doesn’t ‘look disabled’ doesn’t mean that they aren’t suffering or having difficulties. I think, any ripple we can create contributes to the greater good, even just to change one opinion – it’s really important to give people with disabilities a voice. One thing I really love and mention in the show is that, in Dubai, they refer to disabled people as ‘people of determination’. I mean, isn’t that wonderful language?

I know there’re many organisations trying to bring this kind of change to people’s consciousness and I’d love to get involved somehow in the future.

Up until now you have not revealed to anyone in the industry that you have M.S. How did you manage to hide it for so long?

Psychologically it’s been really hard to accept, not only chronic pain, which is always there, but that I always felt terrible about lying. Anyone who knows me knows that I’m usually completely open about everything. So, to hide it over the years was a real challenge for me. One minute it was a ‘sporting injury’, the next I’m thinking, a sporting injury? Is anyone really gonna buy that? Maybe I fell in the shower. I’d just come up with all sorts of stupid ideas. At one point I thought to joke about it, being Australian, and say it was a shark attack or something but, yeah, it was hard. I just felt like I was really going against my integrity.

I’d love for the industry to find a way of being more inclusive of people with disabilities. If I were an accountant, things would be done to make sure I was able to carry out my work but, in the arts, it’s often that ‘time is money’ kind of attitude that holds people back. And it’s such a competitive industry. If there’s an opportunity to bring you down for their own gain, people will. And in some respects, it’s like, why wouldn’t they cast the person who doesn’t have any extra requirements?

I’m actually doing a self-tape tomorrow and it’s that thing of having to decide whether I’m going to be polite and not say anything or whether the agency will get angry at me if I bring my little stool along to the shoot. I mean, I’ve been on commercials in freezing weather where they happily give you woolly robes to whip on and off in-between takes. It should be the same – I’m not causing any problem to the filming by sitting down while the camera’s not rolling.

I’ll keep you posted if I get the part or not (chuckles).

“I’m not gonna be embarrassed to get in my wheelchair and do some bloody shopping.”

Teresa De Gennaro

Would you say it’s important that people are transparent about their M.S. in the performing arts?

It’s a totally individual thing – I think it depends on what part of the industry you’re in. Unless you’re really prepared to accept the fact that people will throw you under the bus, then I’d say hide it if you have to.

I’ve reached a point where I don’t care if it reduces my job opportunities because I’ve had enough of pretending to be somebody I’m not, you know, I’m not gonna be embarrassed to get in my wheelchair and do some bloody shopping. But as much as I’d love to say, ‘Be open, be free with who you tell’, it’s not that simple and depending on what you wanna do, you might just have to work around it somehow until you’re in a position where you’re comfortable to expose that part of yourself.

When I was in London, I was working on a show and had a muscle spasm during rehearsals. I was gonna lie and say it was a freak thing, but a lawyer friend of mine said they technically couldn’t fire me, so I told them I had M.S. As soon as they found out they tried to fire me, which thankfully they had to go back on after I informed them that it wasn’t legal for them to do so.

But they made the rest of the job hell. The director treated me badly, I was excluded from things, it was awful. So, it depends on the situation, where you are in your career, how much you can handle biting your upper lip when you’re in pain.

What advice would you give young people who have M.S. and may wish to go into show business?

Firstly, if you’ve recently been diagnosed, don’t just take one doctor’s advice – do your own research. Try to find a neurologist who specialises in treating M.S. It’ll save you valuable time figuring out what are the most effective treatments for you. Specialised clinics usually have nurses on call who can advise you if you get symptoms that you don’t know how to handle. And if you haven’t already, join your local M.S. society. They’ll be able to get you on the right path.

If you have M.S. and you wanna go into show business, try not to listen to those negative voices. Embrace your hopes and dreams – it’ll be so fulfilling, even if it’s within a certain capacity. Maybe you wanna be a rock star, for example, but you find a way to perform your shows online. You know, there’s always a way to do what you want to some degree.

Meditate as much as you can, eat healthy and make sure you’re getting enough sleep – don’t deny yourself that, if you need it. Looking after your mental health is so important too. Sometimes, the safe option doesn’t really help you after all because you end up just going mad.

Do as much physical exercise as is possible for you – keep that muscle mass so that when you do have a relapse you don’t just waste away. But mostly, I cannot express enough just to not give up on your dreams because in some capacity you’ll be able to achieve them, you know, you can make it a reality. As my dad always says (puts on a thick Italian accent) ‘Everything is possible.’